From an ancient bridge over the River Don to Sheffield’s first railway station, with plenty of history in between - Wicker, similarly to The Moor which I also looked at recently, has seen many changes on a short stretch of road over a long history. Unlike The Moor the origin of the name ‘Wicker’ is a mystery, although it is certainly an old name; it appears on the 1736 Town Plan, the first street map made of Sheffield town centre. Several suggestions have been made, including wicker baskets being made from reeds along the river, and theories surrounding the old English words wick and wic, which commonly appear in place names. Peter Harvey, in his ‘Street Names of Sheffield’ traces a derivation of ‘wick’ to meaning ‘the land near a castle’ which I like, as for centuries Sheffield Castle looked over the area that became the Wicker.

The earliest references to the area are as ‘Sembly (or Assembly) Green’, with the only building on what is now the Wicker being the similarly named Sembley House. Records from Sheffield Town Trust show that archery was being practised on the green in the sixteenth century, and it also appears to have been a parading ground on important days for the town. It was certainly a convenient open space, with large crowds (and the archers) appreciating the location close to the old town centre. Assembly Green was reached by crossing Lady’s Bridge, where there had been a wooden crossing since the late 1100s, and a stone bridge since 1485. The bridge is named after a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary that formerly stood adjacent to it. Lady’s Bridge has been widened and strengthened many times over the years, but earlier versions of the bridge can still be seen from underneath, remaining contained within the current structure.

Looking down the Wicker from Lady’s Bridge in 1896

The Wicker’s long association with Sheffield’s railway history had begun on October 31st 1838, when the first station in the town opened at the junction of Spital Hill and Savile Street. Wicker Station was the terminus of the Sheffield and Rotherham Railway, which enabled Sheffield to be connected to the new Midland Railway. This would have seen a large increase in use of the Wicker, with a reported 75,000 people using the station in the final two months of 1838. Wicker was Sheffield’s only station until 1845 when the connection with Manchester was completed, with the nearby Bridgehouses Station the terminus of that line. Shortly afterwards plans were made for a larger station, Sheffield Victoria, positioned alongside the Wicker. The new station was eventually opened in 1851, but to enable the line to extend that far the viaduct that includes Wicker Arches was built, from Bridgehouses Station to Sheffield Victoria and beyond.

The only surviving image of Wicker Station

It is interesting to think that when Wicker Station was opened the construction mostly associated with the road, the Wicker Arches, didn’t yet exist. There are no surviving photographs of the Wicker pre-arches (or of Wicker Station) and it isn’t easy today to picture the view without them. The iconic arches were engineered by John Fowler, who was later responsible for the Forth Bridge amongst other things. Fowler was born in Wadsley in 1817, and the arches completed in 1848 - so he was still a relatively young man. He would also go on to be instrumental in building the Metropolitan Railway in London, the world’s first underground line. The arches bear the crest of the Duke of Norfolk, and the name of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway. Many will also know that there is still a large patch under the main arch where a Second World War bomb hit the structure. The viaduct is a historic and important Sheffield construction - engineered by an eminent and great Sheffielder.

The brand new Wicker Arches

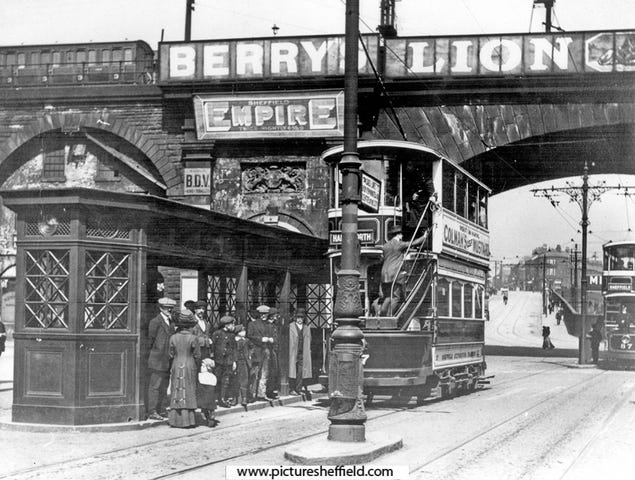

Like The Moor, the Wicker has a long association with Sheffield’s tram history. The first horse tram line to Attercliffe ran down the road in 1873, and electric trams then made their way along Wicker, heading to the east end, for six decades. In the first half of the twentieth century Wicker had tram shelters and cabman’s shelters, alongside the trams, buses, cabs, and cars - and all passing under a still active passenger rail line from Sheffield Victoria to Manchester. Victoria Station had a passenger entrance and lift on the Wicker, just before the arches, and even after Wicker Station closed to passengers in 1870 it stayed in use as a goods yard until 1965. Sheffield Victoria itself closed at the beginning of 1970, apart from coming in useful for the occasional diverted service as the station’s infrastructure remained in place until the mid-1980s.

Trams and trains at the Wicker Arches in 1905

In the mid twentieth century the Wicker was host to half a dozen pubs and a cinema. This wasn’t unusual for a Sheffield street, but it was one of the most popular places for a night out - or a pub crawl. The Wicker Picture House was on the right heading out of town, not far from the arches. It opened in 1920, the same year as Abbeydale Picture House and several others Sheffield cinemas. In later times it became ‘Studio 7’ and was known for more adult themes! Two of the pubs in particular are part of our story; the former Station Hotel next to the arches was named after the original Wicker Station, although for a long time was co-incidentally opposite the Wicker entrance to Victoria Station. The Bull and Oak was lost to the relief road (later named Derek Dooley Way) being built across the Wicker - the pub had stood on the site of Sembley House, the historic original building in the area.

There are still at least a couple of buildings on the Wicker with a story. Imran’s, a well known takeaway, was formerly Friedrich’s pork butchers. Pleasingly the original ‘E.F 1904’ and motif can still be clearly seen on the top corner of the shop. At number 48 stands one of my favourite Sheffield buildings; now the S.A.D.A.C.C.A community centre, it was built in 1853 for John Shortridge and his partners. The frontage of the building contains the date and several pieces of attractive detail, carved above the doors and windows. He was an important character in Sheffield at the time - his previous construction company had been involved in the building of the viaduct that includes the Wicker arches. Shortridge had a grand property built just off Abbeydale Road in 1851, which he called Chipping House, with the road of the same name being close to the site today. He was killed in a road accident near his home in 1869.

No.48 Wicker - built for John Shortridge in 1853

The proximity to the River Don has meant the Wicker has flooded several times over the years. The Great Flood in March 1864 saw Lady’s Bridge somehow survive the impact that had destroyed Ball Street bridge at Kelham Island and the Iron Bridge at Bridgehouses. A contemporary report describes a man near the bridge ‘clinging to a lamp post in order to avoid being carried away, and there he perished’ and the general scene on the Wicker as ‘the shutters of many of the shops were washed down, the doors burst open, and the contents of the shops carried away or destroyed’ (A Complete History of the Great Flood at Sheffield; Harrison, 1864). In July 2007 a 68 year old man was killed on the Wicker during the floods that swept the area. Sheffield has been prone to flooding over the years, and despite modern safety measures the weather still sometimes pushes our rivers beyond their breaking point.

The Wicker Arches are a neglected piece of Sheffield heritage. They are not alone in that of course, and just up the road is the old Town Hall which has been the subject of much controversy over it’s condition and future. I don’t think as much attention has been focused on the arches - and I think it should. Not only are they an important piece of railway history, built by a famous Sheffield engineer who we should celebrate, but they were for a long time a grand entrance to the old town. They also marked the gateway to the industrial east end, and maybe the declining importance of that part of Sheffield hasn’t helped the status of the arches. Unfortunately that side of the city centre has also suffered generally in recent years, and I do think the old Town Hall would have been better protected had it been on Fargate for example. The Castle site plans may help regenerate that area, and I hope there is also a brighter future for the Wicker Arches. People often run the Wicker area down, and a part of our history is also now run down. I’d suggest that smartening up the arches could help recover some pride in a historic road - as well as our having once again a grand entrance to the city.