I’ve seen a few versions of what is an oft-repeated Sheffield tale, but they all seem to agree on one thing; in 1800 no less than King George III himself uttered the above words about Sheffield. The King was said to have been strolling along the seafront at Weymouth (I’ve seen Brighton in one version) when he asked about a family he had come across. Told they were from Norton near Sheffield, he replied ‘Damn bad place Sheffield’. The visitors were the Shores, a prominent society family. Harsh words in several ways - firstly Norton wasn’t in Sheffield at the time, or even in the same county, so the family may not have had much to do with the old town themselves. They also lived in considerable comfort in a grand house, Norton Hall - maybe they were slighted by the words, more likely they agreed with the King’s sentiment.

https://gencem.org/stories/the-shore-sisters/

Definitely not a ‘bad place’ - the old Norton Hall owned by the Shore family

So, why would the nation’s great and good view Sheffield at the turn of the nineteenth century as a ‘damn bad place’? The King was almost certainly referring to the rebellious, even revolutionary, mood of the old town. There was a good deal of support in Sheffield for the French Revolution of 1789, and there were riots following the enclosure of common land in 1791 - leading to the construction of the first Sheffield Barracks at Hillfoot (along present day Infirmary Road). Sheffield was without doubt somewhere that was seen as difficult and problematic by the rich and powerful - and, it seems, all the way up to King George himself. He appears to have been talking about the Sheffield people, rather than the state of the town itself.

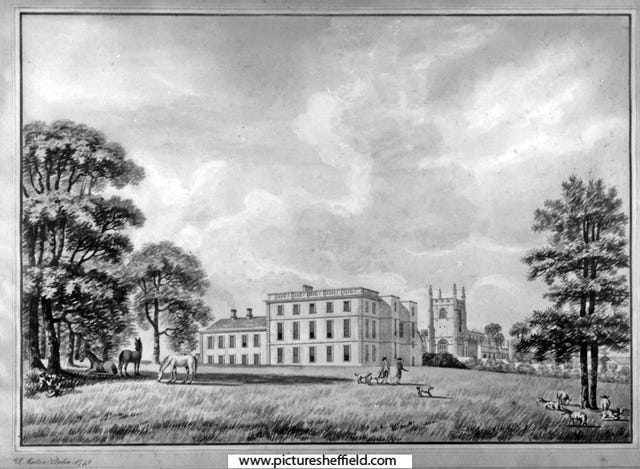

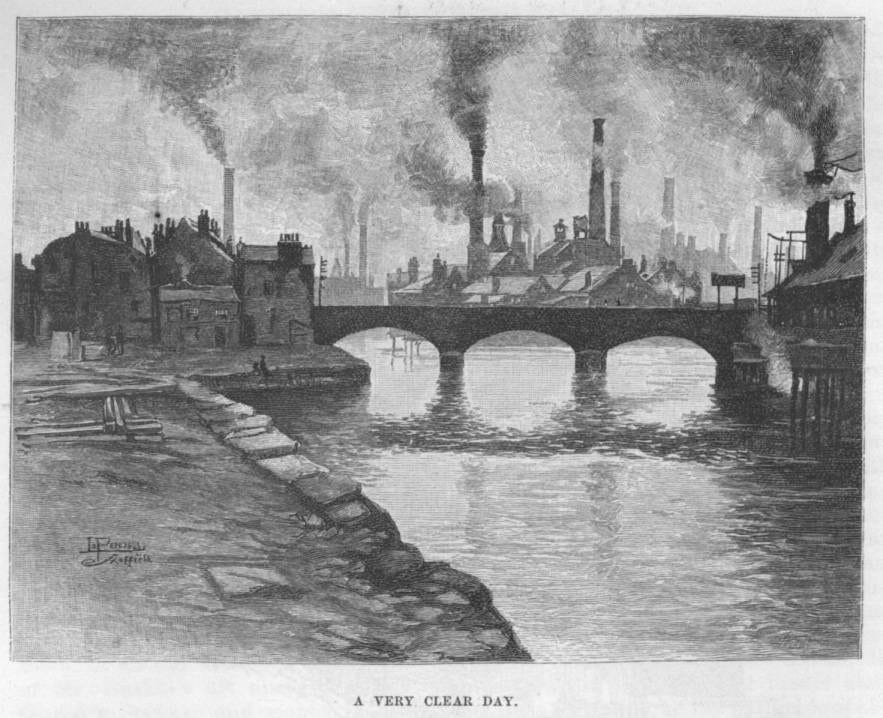

Even prior to the King’s remark there had been several other less than favourable observations of Sheffield in print, and by an impressive cast list of names too. In 1711 Daniel Defoe described the town he visited as; ‘populous and large, with narrow streets and houses darkened black from the smoke of the forges’. Horace Walpole, writer and son of Britain’s first Prime Minister, wrote in 1760 that the town was ‘one of the foulest in England’. This time it is the physical dirtiness of the town that attracts the observations. The local population were more used to living and working in the smoky environment than their esteemed visitors - in 1725 workers claimed to the visiting Earl of Oxford that the ever-present smoke protected them from disease.

A jokey depiction of a ‘very clear day’ in Sheffield

The Sheffield of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was often seen as either rebellious or dirty - or both. To well-off people living in other parts of the country both of these seemed very unappealing, or at least very different to their own lives. Another linked aspect is the poverty - and this is where the city’s most well known later detractor comes in, following the very short stay in Sheffield of George Orwell in 1936. In January that year Orwell’s publisher paid him to tour industrial towns and cities to research the book that became ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’, and he stayed here for just three days between March 2nd and 4th.

I like Orwell very much. I’ve read all his books, and much of his journalism - as a result I’m somewhat loathe to criticise his work; but here goes. He makes several rushed observations about the city, which can only have been made without a thorough look. For example; Sheffield has ‘fewer decent buildings than the average East Anglian village’ - which is clearly untrue. Elsewhere (after just a couple of days) he wrote in his dairies that he has ‘now traversed almost the whole city’, and yet he infamously says about Sheffield that ‘it could justly claim to be the ugliest town in the old world’ - he clearly didn’t visit the Rivelin Valley, or the Botanical Gardens, or Norfolk Park, to pick just a few of the many examples not far out of his way.

Of course Orwell was engaged in journalism here, and a little propaganda too. He was right to highlight the poor living and working conditions in industrial towns, and he spoke with the people themselves - as well as staying in their homes. He lodged at 154 Wallace Road on Parkwood Springs - the street still exists, but not the houses. He was shown the city that the poorer inhabitants knew, so maybe it was his guides who weren’t as familiar with the nicer places in Sheffield. I don’t think that a more balanced view would have taken away from his message - if anything it may have added to it. He could have contrasted the poverty he found with the more leafy and well-off parts of the city, rather than giving an impression of the whole city being poor and rundown.

Wallace Road, Parkwood Springs; where George Orwell stayed whilst in Sheffield

Both Defoe and Walpole did also note the beautiful scenery that surrounds Sheffield, and the marked contrast between the old town’s green surroundings and its grimy appearance may have served to highlight the latter. Writing a couple of centuries later Orwell, who almost certainly arrived by train, is unflattering about the surrounding suburbs too - the earlier writers had seen more pleasant outskirts. Also writing in the 1930s J.B Priestley described Sheffield from what appears to be a safe vantage point on the hills; ‘Sheffield, far below, looked like the interior of an active volcano…the smoke was so thick that it made a foggy twilight in the streets…’ - which seems to make the point about the stark contrast. It was quite possible to describe the dirtiness of the town without even entering!

Those learned observers of Sheffield over the years had often not been here before, and maybe not to many similar places either. Orwell is said to have never been this far north before his research in 1936. There may have been a natural tendency to confirm their preconceptions about the industrial heartlands. This brings me to the perception of Sheffield generally, and how different it is from the reality. I grew up in the south and had no idea whatsoever of how nice the area is, however I know plenty of people who moved here for the opposite reason; they had often visited the area and knew what it had to offer. The city remains a well-kept secret to many, even sometimes to Sheffield folk themselves who often relate to me negative views of their home city.

The attitudes I referred to at the top of the page as ‘disparaging’ revolved around two main themes; industry and rebellion - neither of which are in any way shameful. ‘Dirty’ Sheffield is the same as industrial Sheffield; the Steel City - we couldn’t have been one without the other. These critics would likely have used and owned Sheffield made products, made here in those same ‘dirty’ streets by the same people. I think we know Sheffield people are pretty straight talking, but also capable of being self-deprecating too, and as a result have probably never been very bothered by the critical views of outsiders. Returning to the utterance of King George III, his words aren’t disparaging in the same way as the others quoted; he was (presumably) telling Sheffield people off for standing up for themselves, and for showing solidarity with others - characteristics that have recurred through Sheffield’s history. I consider that his words were, and remain, a badge of honour.

Sorry George, but really…

I've just read The Road to Wigan Pier, and if living conditions for some in Sheffield were half as bad as Orwell reports, they were dire beyond belief. And this was less than 100years ago. My mother was a child in 1936!

We can't condemn the workers who lived in these conditions though, but we can strongly condemn those that kept them in such poverty- the landlords, land-owners, industrialists and investors. Some things don't change, I'm sure they'd do the same now in pursuit of a quick profit!

I may not - well, don’t - live in a stately home, but I do live in Norton. We don’t seem to be that rebellious these days, being mostly of mature years, but I for one am eternally thankful for the fierce pride of the Sheffielders of yesteryear. Without such people asserting their right to be seen as human beings just the same as all the rich people (including the king!), we might still be breathing filthy air, living in slums and often being cold and hungry.

(Having said that, of course some people do still live in awful conditions. It angers me that the wealthy are so often reluctant to make much of a contribution to helping their fellow citizens.)